News

Node Spotlight - Antarctic OBIS, connecting Antarctic marine biodiversity data to the world

14 December 2025

Ice fish Larvae collected during the BROKE-West Expedition onboard RV Aurora Australis. Photo: ©Anton Van de Putte

Ice fish Larvae collected during the BROKE-West Expedition onboard RV Aurora Australis. Photo: ©Anton Van de Putte

The Southern Ocean is a region of extremes: vast, remote, and ecologically unique. It’s a place where every observation collected requires significant effort and resources. The Antarctic OBIS Node ensures that this data is preserved, shared, and made accessible for science, management, conservation, and policy. As one of the longest-running OBIS Nodes and among the first to operate as a dual OBIS-GBIF Node, Antarctic OBIS has spent nearly two decades assembling, standardizing, and publishing open biodiversity data from expeditions, monitoring programmes, and international collaborations.

We spoke with Anton Van de Putte (OceanExpert / Orcid), Manager of Antarctic OBIS, and Yi-Ming Gan (OceanExpert / Orcid), Data Manager of Antarctic OBIS, to learn more about the Node’s origins, role in the Arctic scientific landscape, and the challenges of managing polar biodiversity data.

OBIS Node Spotlight is a new series of articles on our website that shines a light on the people working behind the scenes at OBIS Nodes. From building local capacity and supporting data providers to mobilising, standardising, curating, and publishing marine biodiversity data, as well as supporting field campaigns and expeditions, the series lifts the veil on the everyday work of OBIS Nodes.

OBIS: When was the Antarctic OBIS Node created?

Anton Van de Putte: Antarctic OBIS was established around 2006 by Claude De Broyer and Bruno Danis as part of the Census of Antarctic Marine Life. It originated from two foundational initiatives: the Register of Antarctic Marine Species (RAMS), developed within the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS), and SCAR-MarBIN, the Special Committee on Antarctic Research Marine Biodiversity Information Network. Since 2012, Antarctic OBIS has also served as a GBIF node, which enabled the SCAR Antarctic Biodiversity Portal to integrate marine and terrestrial data.

What motivated the creation of the Antarctic OBIS Node?

Anton Van de Putte: A number of factors came together. The idea of openly accessible biodiversity data in Antarctica dates back to the Antarctic Treaty of 1959: Article III(1)(c) states that scientific observations and results must be exchanged and made freely available. By the early 2000s, scientific activity in Arctica was increasing rapidly, raising the question of how to preserve and share this growing volume of biodiversity data.

The solution was to create a neutral, regional data initiative where scientists could deposit their marine biodiversity data: Antarctic OBIS. The Node operates under the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research, reinforcing our commitment to Open Science principles, and enables us to provide independent, objective scientific information for evidence-based decision-making.

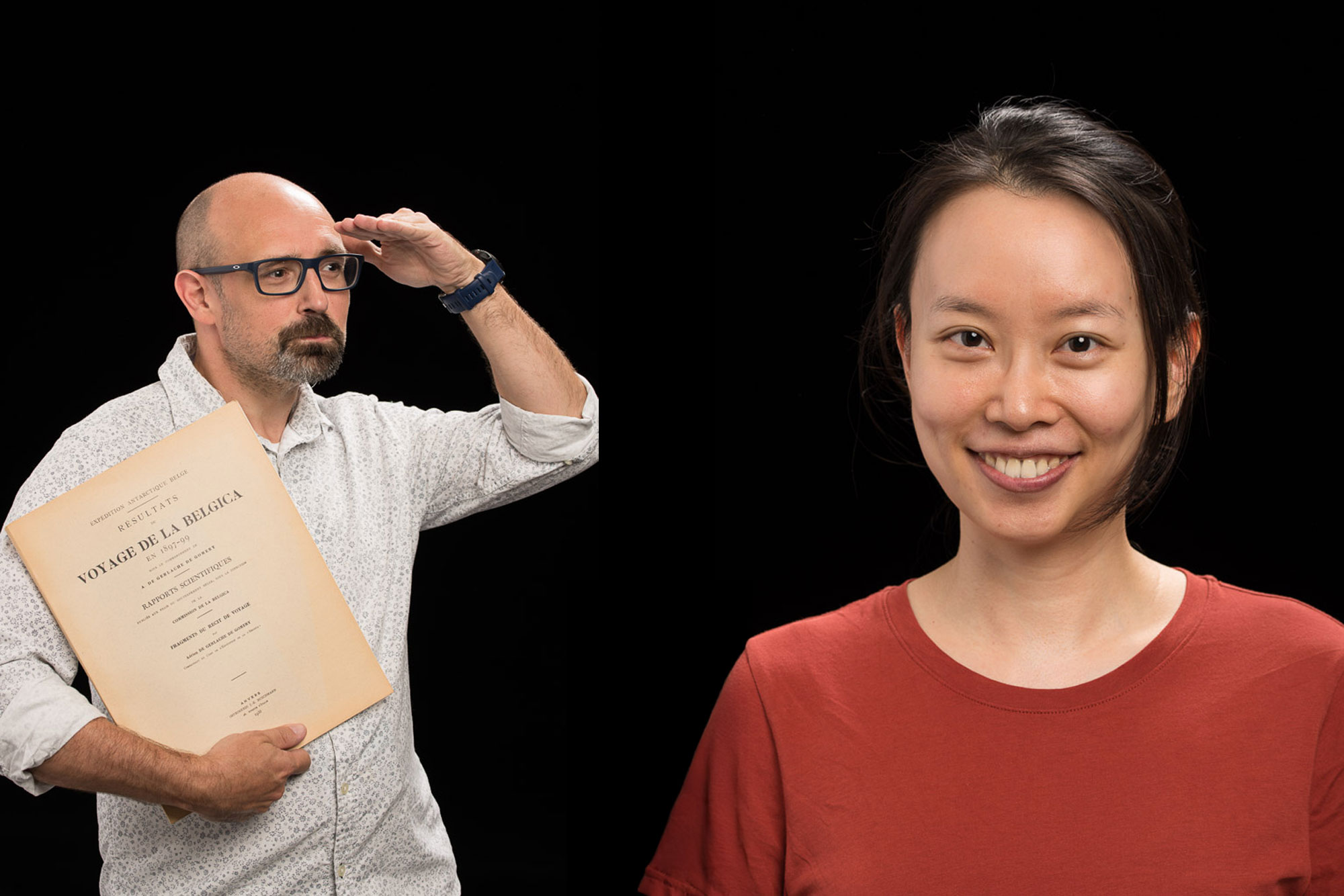

Anton Van de Putte (left), Manager of Antarctic OBIS, and Yi-Ming Gan (right), Data Manager of Antarctic OBIS

Anton Van de Putte (left), Manager of Antarctic OBIS, and Yi-Ming Gan (right), Data Manager of Antarctic OBIS

When did you join the team?

Anton Van de Putte: I joined Antarctic OBIS in 2011, to support data management and publication, and became the Node Manager when Bruno Danis moved to a university position.

Yi-Ming Gan: I joined in 2017 as a web developer/data manager. Over time, my work has shifted almost entirely to data management. After Anton, I’m now the second-longest-serving member of the team!

Anton Van de Putte: Our team also includes colleagues working on data products, such as Pablo Deschepper (OceanExpert / Orcid) and Charlie Plasman (OceanExpert / Orcid) who are developing tools to support Essential Ocean Variables.

Scientific interest in Antarctica has grown significantly. How do you cope with the increasing demand?

Anton Van de Putte: Antarctic OBIS is one of the oldest Nodes in the OBIS Community and one of the first to operate jointly with GBIF. This experience has given us the flexibility to accommodate many situations. Our goal is simply that marine biodiversity data from the region reaches OBIS and GBIF, regardless of the pathway. As a regional node, we do not require anyone to publish through us. Instead, we offer a range of services depending on national structures and capacities. In countries without a national OBIS Node, such as Italy, we have provided training and direct support. Italian researchers now prepare their data in accordance with the OBIS Manual, and we publish their datasets via our IPT while maintaining their ownership. Their datasets today require minimal correction.In countries with a national OBIS Node, we often assist data curation—this is mostly Ming’s work—and the data are then published through that national Node directly. Australia is a good example. The Australian Antarctic Division (AAD) manages Antarctic research, logistics, and data. A biological observation dataset linked to an Antarctic expedition needs to be published through the Australian Antarctic Data Centre. When a dataset is linked to marine biodiversity, it also needs to go to OBIS Australia. Because of our existing relationships with Antarctic researchers, we have helped Australian Antarctic Expedition researchers to standardise data, which is then published formally through the Australian Antarctic Data Centre and pushed to OBIS Australia. We also support SCAR-wide initiatives that integrate data from many sources. One major example is the Retrospective Analysis of Antarctic Tracking Data project (RAATD), which compiled 10 years of tracking data from across the Antarctic research community into a single, openly available dataset.

How do you work with the data? Do scientists contact you directly?

Yi-Ming Gan: Most of the data we publish comes from research cruises or long-term monitoring programmes, such as counts of penguins, seals, and other Southern Ocean species. A large part of our work involves speaking directly with scientists, explaining what Antarctic OBIS does, and encouraging them to publish their data. We promote open data and FAIR principles at conferences. After talks related to Antarctic biodiversity, Anton often speaks with presenters about submitting their data. Many of our collaborations begin this way.

Could you share a highlight from your time at Antarctic OBIS?

Yi-Ming Gan: For me, it’s the BROKE-West fish dataset, without hesitation. It comes from Anton’s PhD. We had many discussions about this dataset, and I learned a lot from them.

The dataset was originally a simple occurrence table published in 2008. It then became a test case for several key developments: the Extended Measurement or Fact (eMoF) extension, the Humboldt extension, and eventually the Darwin Core Data Package. Through this process and the related discussions, I learned a lot about how data is collected on cruises, how it is structured in sample management systems, and how to translate it into operable, actionable formats.

Anton Van de Putte: For me, two datasets come to mind. The first one is indeed the BROKE-West dataset, although for a different reason than the one Ming mentioned. Before BROKE-West, there had been the BROKE-East expedition. When I tried to compare results from the two, I could not access the underlying data. I contacted seven members of the original team, but none could provide what I needed for my analysis. That experience showed me how vital Open Science is. My second highlight is Myctobase, a circum-Antarctic database of mesopelagic fish. I worked together with Bree Woods (Orcid). She did the work I had not had time to do during my PhD: bringing together existing datasets, standardising them, and analysing them. In 20222, we completed a project idea that originally began in 2006-2007. Myctobase now provides a very complete overview of mesopelagic fish distributions around the Antarctic.

What challenges do you face in obtaining and managing data?

Anton Van de Putte: Data management often comes at the end of a project, when there is no funding left and when deadlines are tight. Discussion about how to manage data should happen during the preparation phase of an expedition, not when a project is about to be completed. But this is rarely the case.

Yi-Ming Gan: There is a financial paradox: project data is expected to live forever, but funding only lasts for the duration of the project. Sustaining data beyond that requires long-term resources. We often receive data long after a project ends, or we must rush to publish it before a deadline. Better planning and anticipation would solve a lot of these issues.

Anton Van de Putte: We have no authority to require data submission. Our work is based on collaboration. We provide advice whenever possible, but more substantial work depends on available funding.

Do you collaborate with other OBIS nodes?

Yi-Ming Gan: Yes! We worked closely with OBIS-USA to develop a pipeline for long-term penguin and seal monitoring data, enabling automated generation of Darwin Core tables that can be published through the OBIS-USA IPT and directly archived at the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). We are also initiating a collaboration with OBIS Japan. The Japanese Polar Data Center invited us to present our work at their symposium, and we hope to support them in publishing their Antarctic biodiversity data through OBIS and GBIF.

Anton Van de Putte: We have collaborated extensively with the British Antarctic Survey and are having conversations with India through IndOBIS, Chile, and South Africa. Our approach is to understand national structures and existing pathways. We try to identify what support is needed and build a workflow suited for each country’s specific context.

What does being part of OBIS mean for you?

Anton Van de Putte: We have always been an OBIS Node; it is our natural environment. Support from the Secretariat and interaction with other Nodes through the Steering Group and coordination groups meetings have been extremely valuable to us. At the same time, we are also part of the SCAR community, which operates very differently from the UN system. It took us time to understand how OBIS functions within UNESCO and the UN frameworks.

Yi-Ming Gan: Engaging with OBIS helped me grow professionally. Chairing the Data Quality Assessment and Enhancement Project Team, now the OBIS Data Coordination Group, pushed me to deepen my technical knowledge on data and formats, and gave me the confidence to take on leadership roles. Thanks to that experience, I can now give back and help the Community.

Sunset in de Weddell Sea during EWOS expedition Onboard FS Polarstern, 2022. Photo: ©Anton Van de Putte

Sunset in de Weddell Sea during EWOS expedition Onboard FS Polarstern, 2022. Photo: ©Anton Van de Putte

What is ahead for Antarctic OBIS?

Anton Van de Putte: The coming years will be very active for Antarctic observations. The Antarctica InSync project, beginning in 2027, is closely linked to Essential Ocean Variables, a strategic development for OBIS. The next International Polar Year will take place in 2032. We are also very much focused on developing policy-support products for the region, such as contributions to the RED database, as well as the state-of-the-environment reporting for the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) and the

Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM). Essential variables and dashboards integrating OBIS and other environmental data will be central to this work.

Would you like to add something? A message you want to share?

Yi-Ming Gan: I want to speak about gender equality. In many professional settings related to data, I still see a clear imbalance, with fewer women represented. We need to address that imbalance and empower more women in this field.

Anton Van de Putte: I agree with Ming. Data management remains a male-dominated area, and we need to improve representation. Supporting early-career women and providing leadership opportunities makes a real difference.

◼️

→ Dive deeper under the ice!

These selected publications offer deeper insights into the data, methods, and collaborations suporting our understanding of Antarctic marine ecosystems.

Ropert-Coudert, Y., Van de Putte, A.P., Reisinger, R.R. et al. The retrospective analysis of Antarctic tracking data project. Sci Data 7, 94 (2020)

Hindell, M.A., Reisinger, R.R., Ropert-Coudert, Y. et al. Tracking of marine predators to protect Southern Ocean ecosystems. Nature 580, 87–92 (2020)

Woods, B., Trebilco, R., Walters, A. et al. Myctobase, a circumpolar database of mesopelagic fishes for new insights into deep pelagic prey fields. Sci Data 9, 404 (2022)